THE HISTORY OF MINOLTA

THE TWENTIES

Minolta was formed in 1928, as the Nichi-Doku (which means "Japan-German") Shashinki Shokai ("Photographic Company") by Mr. Kazuo Tashima. It was appropriately named since their first camera, the Nicalette of 1929,

had a German-made lens and a German-made shutter. But Minolta is well-known for many "FIRST"s in photographic history, as you will see!

THE THIRTIES

In 1931, the name of the company was changed to "Molta Goshi Kaisha", and the name "Minolta" was legally registered which means "ripening rice fields". In the 1930s, cameras were large and bulky. The most popular cameras folded up for easy storage and transport. So in 1934, Minolta made the Vest and Best. They were, in fact, the same camera.

It was a folding camera, but with a difference. Up to this point, folding cameras always used leather bellows which were relatively expensive. Minolta was the first to use a system of plastic sections in decreasing size that collapsed into each other, making the camera small and inexpensive.

Also in 1934, Minolta created the first Japanese camera to use the 6x4.5cm format. This was the Semi (meaning "half-frame") Minolta I.

Also popular in the 1930s were the German, Rollei, TLR cameras. Minolta's first camera of this design was the Minoltaflex of 1936.

It stood out because it was the first TLR made in Japan to have a double-exposure prevention mechanism.

In 1937, "Minolta" changed its name once again, this time to "Chiyoda Kogaku Seiko". It was also the year that Minolta started to manufacture some of its own lenses. Before this, it obtained most of its optics from Asahi -- Japan's largest glass maker.

THE FORTIES

The first Minolta-made lens with the "Rokkor" name appeared in 1940 on a portable aerial camera used for military purposes. The "Rokkor" name was in honor of Mt. Rokko, which could be seen from the Minolta plant. The lens was a 200mm f4.5 Rokkor copied after the Gernam Zeiss-Tessar design. Minolta's military sales soon helped it build its first separate optical plant in 1942. But by the end of WWII, the Japanese economy was in ruins. Minolta was relatively quick in recovering and produced the first post-war camera in Japan -- the Minolta Semi IIIa -- in 1946.

In the same year, they produced the first coated lenses in Japan. The next year, 1947, Minolta began making a long-lived series of Leica copies using the new 35mm format. These were simply called "Minolta 35"

and helped establish Minolta as an important player in the photographic realm.

THE FIFTIES

In 1950, a Japanese company named "Konan" began producing a tiny 16mm camera -- the Konan Automat. Soon after, due to financial problems, they sold the rights to Minolta -- which redesigned it and started selling the Minolta Automat 16 in 1955. Two years later, they redesigned it again and created the legendary Minolta 16.

This camera has a number of misconception about it. It was a very common camera and many people assume, for some unknown reason, that it was the only 16mm camera that Minolta made. Others assume that this was the first 16mm camera that Minolta made. Then others spread rumors that this camera was officially used by the CIA, FBI, KGB, James Bond, Gordon Liddy, etc. All of these notions are way off-base. This camera first appeared in 1957 and was made until 1960. It has a 25mm lens with f-stops from f3.5 to f11. It also has three speeds of 1/25, 1/50, and 1/200. The camera was available in seven stunning colors -- chrome, black, gold/yellow, blue, red, purple/magenta and green. The camera sold for just $9.95 and became so popular that it led to a wide variety of Minolta 16mm cameras until the mid-1970s. It was replaced by the uodated Minolta 16 (model II), and in many ways it laid the groundwork for the later 110 and disc cameras of the 1970's and 80's -- small, compact cameras that can go anywhere.

But back to the 1950's. In 1955. Minolta unveiled the first Japanese camera to be fitted with an EV-based exposure meter -- the Autocord L. And in 1958, it produced the first Japanese camera with a a fully-integrated, internal, coupled, meter -- the Autowide. Taking pictures was getting easier, and easier.

By 1958, the Japanese camera industry was exploding with energy. In this year, Minolta pioneered the first Achromatic Coating -- two layers of magnesium fluoride deposited in different thicknesses to radically reduce glare and flare. In reality it was the world's first multi-coating. At the same time, other companies started marketing their new SLR cameras, such as the Asahiflex, Pentaflex, Miranda T, Topcon R and Zunow. These SLRs were selling quite well around the world despite having to compete with quality German SLR cameras. At the time, Minolta was a recognized camera company, but they didn't make an SLR camera. Their sales were mainly in TLRs, Leica copies and 16mm subminiature cameras. The SR-2 was Minolta's first venture into the world of the SLR.

It was a giant gamble for Minolta. Marketing an SLR -- a very expensive proposition -- would mean disaster for the company if it were a flop! Minolta understood this, and made an SLR that was a giant leap ahead for the company -- and for the marketability of the SLR camera in the world of photography. Sure, other companies offered SLR cameras with interchangeable lenses, but these cameras were rather clumsy to use. They lacked most of the convenience features that we take for granted today. For example, most SLR cameras of the time lacked an instant return mirror. After each picture, the mirror remained in the "up" position and the viewfinder was blacked-out until the film was advanced.

In addition, mechanically, lenses were much simpler and not coupled to the camera in any way. Today, we call these lenses, "manual lenses". Whenever the lens was stopped-down, the camera viewfinder got dark. Using small f-stops was a real challenge as the viewfinder quickly became useless. Manufacturers "solved" the problem in one of two ways -- each more awkward than the other. One approach, sometimes referred to as "semi-automatic", required the SLR photographer to cock the lens -- moving a lever on the side of the lens to set it at the largest f-stop -- after cocking the shutter on the camera. This kept the lens open to the maximum aperture until the picture was taken. A small lever in the camera released the lens just before the exposure was taken. But separately cocking the shutter and the lens was time-consuming and awkward. The other approach is referred to as "pre-set". These lenses have the standard aperture ring, but add a "pre-set" ring right next to it. On the aperture ring, you dial in the f-stop you want to use for the exposure, but leave the pre-set ring at full aperture. This set-up let's you compose and focus with the lens wide-open. Then, just before taking the picture, the pre-set ring is turned -- which stops the lens down. As with "semi-automatic" lenses, it's pretty awkward and prone to errors. First, fast, spontaneous pictures are impossible. And if you forget to turn the pre-set ring, the exposure is way off. Another problem with early SLR lenses was attaching and removing them from the camera. This was yet another, rather awkward, time-consuming process -- and best accomplished with three hands!

By 1958 Minolta had figured out how to make an easy-to-use SLR, and they hit the ground running. Other manufacturers had to scramble to keep up. It's no secret that the Minolta SR-2 completely changed SLR photography, and made it the wave of the future. That's why it's listed in the book, "The Evolution of the Japanese Camera" (published by the International Museum of Photography at George Eastman House in Rochester, New York) as one of the most important cameras in photographic history. The SR-2 made awkward lenses and blacked-out viewfinders things of the past. All of a sudden SLR cameras were actually fun to use instead of being too technically challenging for most people to master.

With the SR-2, the camera body offers automatic control of the lens diaphragm. This means that the lens remains at full aperture regardless of the f-stop selected -- and without the need to "cock" the lens. The camera stops-down the lens to the chosen f-stop automatically, at the instant of exposure, and the lens is "cocked" automatically when the film is advanced. It's no big deal today, but at the time it was a huge achievement. Actually, the diaphragm action on the SR-2 is best referred to as "semi-automatic". After an exposure, the aperture does not return to it's fully-open position. It is necessary to advance the film for the automatic diaphragm to become engaged. But since the camera lacks a depth-of-field button, this allowed you to check the depth-of-field before advancing the film. In addition, the SR-2 features an instant return mirror. It is no longer necessary to advance the film to see your subject at the maximum f-stop setting. For the first time, these features made using an SLR camera a much more pleasant experience, and pictures could be taken much more quickly.

Finally, the SR-2 had a new, easy to use, bayonet lens mount. Instead of the awkward, time-consuming screw-mounts and breech-mounts used by other manufacturers, the SR-2 offered a quick, three-pronged, bayonet mount. This mount is so simple that it is easy to use with a single hand, and only requires a quick, 54 degree turn to lock the lens in place. Pre-setting anything on the lens or the camera was no longer needed -- well, at least as long as you owned a Minolta! Changing lenses can be done in an instant, even in the dark, making spontaneous SLR photography a reality -- finally.

The SR-2 had a winning combination of features: an instant return mirror with semi-automatic lenses -- only the second Japanese camera to accomplish this feat. Within a decade, Minolta had taken on the "big boys" in photography and was at the forefront of the industry.

THE SIXTIES

By 1961, the writing was on the wall. The Japanese photographic industry had to produce a 35mm SLR with interchangeable lenses AND a built-in meter -- and FAST! Canon did it with the Canonflex RM in 1961, but it had an unresponsive selenium meter. In 1962, Minolta was able to step-up to the plate and market the amazing SR-7.

This was the first Minolta SLR with interchangeable lenses AND and built-in meter. It was a CDS meter to boot! In fact, it was the first Japanese SLR to accomplish this feat. Minolta was once again at the leading edge of the Japanese 35mm SLR market. In this model, the large, external, clip-on meter of the earlier SR-3 is moved inside the camera body, but the size of the camera body did not increase -- a rather remarkable achievement. Admittedly, the meter was not TTL, and the meter readout was on the top of the camera, but it was still quite an accomplishment for the time. To top it off, the meter was coupled to the shutter speed, so exposure adjustment was very easy. First, dial the film speed into the meter. Then select a shutter speed that's appropriate for the subject and setting. Next, point the camera at the subject and the meter's needle points to the correct f-stop. Exposure was never so quick. The SR-7 has a "dual-range" exposure meter. Normally, a metal plate with a tiny hole sits in front of the meter's CDS sensor, which is for high range (i.e. high luminance) readings. By pressing a button on the back of the camera, the plate exposes the full sensor (for poorly lit situations), which also brings up another scale on the meter's f-stop display. So the camera could operate in bright conditions and in very low light, something cameras with built-in selenium meters simply couldn't do. In addition, this camera included a mirror lockup for use with the new super-wide Minolta Rokkor 21mm lens. One of the drawbacks to the use of SLR cameras -- at the time -- was the lack of any wide, wide-angle lenses. A 28mm lens was as wide as you could expect to find on an SLR. The problem was that a super-wide lens had to be so deeply recessed into the camera body that the SLR's mirror would be blocked from moving out of the light path by the back of the lens. (This was not a problem with other types of cameras, such as rangefinders because they lacked the reflex mirror.) Minolta came up with an innovative solution and built a mirror lock-up into the SR-7. By moving the mirror up and out of the way, deeply recessed lenses could be used. Since the mirror was now in the "up" position, the viewfinder was blacked-out and the subject could not be viewed, but Minolta solved this problem by including separate viewfinders with their super-wide 21mm lenses. The viewfinder slips into the flash shoe and shows you, approximately, what will be recorded on the film. But the lock-up feature was not needed for long. The development of retro-focus (inverted telephoto) lenses negated the need for the mirror lock-up and the 21mm lens was the only lens that Minolta made that required the use of the mirror lockup. Minolta would go on to make lenses as short as 7.5mm that do not have a recessed design and do not need the mirror lock-up. But the lockup device continued to appear on many Minolta SLR camera bodies and is useful for other reasons, such as reducing vibrations in macro- and tele-photography.

Also in the early 1960's Minolta made improvements to their line of 16mm cameras. One, the Sonocon, was a combination of a 16mm camera and a transistor radio! In another model, the Minolta 16 EE, for the first time, Minolta offered a 16mm camera with a built-in meter -- AND automatic exposure (shutter-preferred). The size and weight of this 16mm camera was increased substantially, since it had a meter (selenium) and several other new features. The camera used a "manual-programmed/shutter preferred" exposure method. Minolta was soon to come out with an improved version featuring a CDS meter -- the Minolta 16 EE2.

At about the same time, Minolta started making half-frame cameras, such as the Repo, and, for the first time, Minolta was offering a 35mm camera with true automatic exposure -- the Hi-matic.

Although this camera looked the same as previous Minolta rangefinders, it was radically different. It has a built-in selenium meter (EV 8 - 16) that provided programmed automatic exposure of both the aperture and shutter speed from 1/30 at f2.8 to 1/250 at f16. It also offered limited manual exposures setting for flash use -- at 1/60 the f-stops could be set manually. There is even a B setting for timed exposures. Built-in coupled rangefinder, self-timer, cold flash shoe, cable release, tripod socket and PC contact. The Hi-matic can be found with both "Chiyoda Kogaku" or "Minolta" engraving, since Chiyoko changed their name to the Minolta Camera Co. in 1962. A modified Hi-Matic was the first camera in space, taken aboard Friendship 7 by John Glenn.

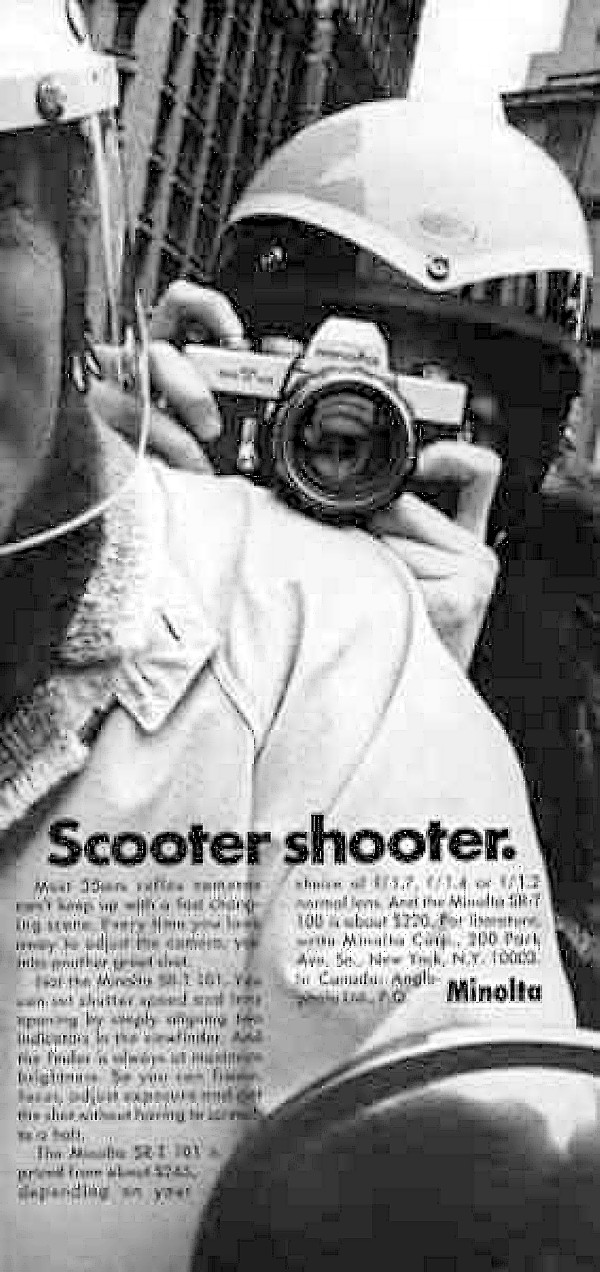

And by 1966, Minolta had finally "done it". It began production of an SLR with a TTL meter, operating with a fully-automatic aperture and interchangeable lenses -- the revolutionary SRT101.

It took the industry by storm and blew away the competition. Sure, there were lots of other German and Japanese 35mm SLR cameras that had auto-diaphragms, interchangeable lenses, and even built-in, TTL meters, but all of them had at least one major drawback. For example, the other camera companies at the time, that were offereing TTL metering, were using awkward, stop-down metering systems, such as the Asahi Spotmatic of 1964, the Nikon Nikkormat of 1965, the Canon FT of 1966 and the Mamiya 1000TL of 1966. So even if their camera sported an auto-diaphragm, the photographer still had to stop-down the lens in order to take a meter reading. In this metering approach, you press a switch on the camera body which stops-down the lens and activates the meter. Only at that point can the meter take a reading. Not only is this process awkward, it defeats the whole purpose of having an automatic lens -- to keep the lens open and the viewfinder bright until the instant of the exposure!

The biggest technical obstacle to developing a TTL metering system with fully automatic lenses is that the meter in the camera needs to know the f-stop setting on the lens -- because an automatic lens always stays at it maximum aperture. The lens and the camera have to be able to "talk" to each another. For most other camera manufacturers, the f-stop ring was placed in the middle or at the front of the lens. This made linking the f-stop ring and the camera's TTL metering system a difficult challenge. For most companies, this would mean redesigning their entire line of SLR lenses. Instead, they offered the consumer stop-down metering, and hoped they wouldn't mind.

Minolta was able to avoid the whole problem of "stop-down" metering because they happened to design most of their Auto-Rokkor lenses -- from the very beginning -- with the aperture ring next to the camera body. By placing a small lug on the Auto-Rokkor f-stop ring, and placing a matching spring-loaded pin on the SRT101 camera body, the problem was solved. The lens conveys the selected f-stop to the camera meter as the aperture ring is turned. A 4mm change in the f-stop ring on the lens changes the TTL meter reading in the camera by one f-stop. The meter is then able to determine the appropriate shutter speed -- for that scene, shutter speed and film speed -- while the lens diaphragm stays open at its maximum setting. This is just one of the reasons why Minolta was able to keep their lens mount the same over all these years, while nearly every other camera manufacturer has had to make significant changes in their lenses.

With this modification, the MC Rokkor lenses were born. Stop-down metering became a thing of the past. Well, at least if you owned a Minolta SRT101! The "MC" in "MC Rokkor" refers to "meter-coupling" -- not "multi-coating", as some people think. These lenses were double-coated, but not multi-coated. The older Rokkor and Auto-Rokkor lenses will fit on the new SRT cameras because the mount is the same, and most will operate correctly, but they cannot couple to the TTL metering system of the SRT101. Metering with non-MC lenses is accomplished in the "stop-down" fashion.

One challenge to the new system was that, since the lenses remain at

the maximum aperture regardless of the pre-set f-stop, there is no way for

the photographer to view the actual depth-of-field in the viewfinder -- as

you could do easily with older lenses by just pressing the built-in DOF button

on the lens. Minolta resolved this problem by adding a new DOF (depth-of-field)

button to their new SRT101 camera. This was an easy item for Minolta

to add since it was a feature that they had already tried out on the Minolta

SR777 prototype. In fact, a stop-down button was

required on the SR777 since it was designed to use

stop-down metering. Pressing the stop-down button, stops an automatic

lens down to the pre-set aperture, so that you can view the actual depth-of-field

in the viewfinder. On cameras with stop-down metering, this button is called

the stop-down metering button, but on Minolta cameras, because it is primarily

used to check depth-of-field, it is referred to as the DOF button.

But the new TTL meter and new meter-coupled lenses were not the end of the

new features of the Minolta SRT101. That would have been enough to

set the industry on fire, but Minolta didn't stop there. The new Minolta

TTL meter readout was moved from the top of the camera, as in the

SR-7, and was placed inside the viewfinder -- an incredible

innovation in miniaturization and convenience. Up until now, photographers

would compose the scene in the viewfinder and then have to drop the camera

to make exposure adjustments -- and then raise the camera again and re-compose.

One word -- S-L-O-W!

In the SRT101, two "needles" were placed on the right-hand side of the viewfinder and connected to the aperture, shutter speed and film speed settings. By changing any of these factors, the needles would match up when the exposure was correct. Just get the needle inside the circle and your exposure will be fine. And to top it off, Minolta added a battery-check tab in the viewfinder, as well as over- and under-metering-range triangles for very bright and very dark situations. Yet another new feature of the SRT101 is that the complete range of shutter speeds (1 second to 1/1,000, plus B) is visible in the viewfinder, so you no longer needed to remove your eye from the viewfinder to adjust the shutter speed -- and take a picture. Other new features included a built-in flash shoe and a switch to turn off the meter -- the latter being a lesson Minolta learned from the SR-7. The other important advances of the SR-7 were retained, such as the mirror lockup for the super-wide 21mm lens, and a self-timer.

Minolta studied thousands of photographs in order to determine the best way to accomplish accurate TTL metering. Different companies had different designs, but Minolta noticed that a large proportion of photographs were really two scenes in one: an upper-half which was often a bright sky, and the lower-half which was typically a darker foreground. Many pictures were incorrectly exposed due to the inclusion of the bright sky which "over-powered" the foreground and caused the meter to underexpose the main subject -- which is usually in the foreground. Minolta devised an innovative solution, with a simple modification to the typical TTL metering system. While most TTL manufacturers used one CDS cell affixed inside the pentaprism, Minolta employed two cells pointed in two directions. This allowed the camera's meter to view, and compare two different areas of the picture. The Minolta engineers determined that the typical exposure could be dramatically improved if the sky-portion of the scene had less effect on the exposure. They were able to accomplish this by having one CDS cell reading the sky (or upper portion of the scene), and a second CDS cell reading the lower-portion of the scene. The brightness of the sky was then easy to control, and no longer overwhelmed the foreground reading. Minolta dubbed the new system "CLC" which stands for "Contrast Light Compensation".

THE SEVENTIES

In the early 1970's, Minolta continued to expand and improve their line of 16mm cameras. In fact, Minolta had the lion's share of the 16mm market. First, they stunned the market with the amazing 16 MG-s in 1970.

Although it was the same size as the previous Minolta 16mm cameras, and used the same film cassette, the images were substantially better because they were bigger! The film format size was increased to 12x17mm -- nearly 50% bigger than the 10x14mm image of the previous models. This was accomplished by using single perforated film instead of double perforated film. The Minolta cassette stayed the same, and the size of the camera did not increase -- quite an accomplishment. The lens was a 4 element, 3 group 23mm (f2.8-16) fixed-focus optic. The focus was set at about 13 feet; the depth-of-field was variable with various close-up lenses (one-built-in) and the f-stop. Shutter speeds of 1/30-1/500. Shutter-preferred automatic and manual exposure modes. This was designed as a "system" camera and had many accessories available: Filters (1A, 80A, Yellow), Closeup Lenses (80cm, 40cm, 25cm), copy stand, spy finder, closeup measuring chains, case, wrist strap, built in closeup lens, built in lens cover, tripod socket, attache case, flash bulb adapter, flash cube adapter, electronic flash adapter.

But what really shocked the photo industry is what Minolta produced in 1972. From 1966 to 1971, the only SLR cameras that Minolta marketed were the incredible SRT101 and the more economical SR-1s & SRT100. These cameras sold well, but Minolta knew that they had to make improvements -- and fast. Specifically, sales of rangefinder cameras were doing much extremely well, compared to SLR cameras, primarily because the rangefinder cameras offered automatic exposure control, while SLR cameras lacked this feature. In short, the rangefinder cameras were smaller, lighter, cheaper and much easier for photographers to use. Just as important, Minolta knew that other camera companies would soon figure out how to add TTL, automatic exposure control to their SLR cameras.

Minolta saw an opening in the market and jumped on it. In late 1972, they marketed the incredible XK camera.

With such a new, advanced feature as automatic exposure control, Minolta targeted the professional camera market, at that time dominated by Nikon and Canon. The XK was the first professional SLR camera with TTL, automatic exposure control. "Revolutionary", was what the reviewers called it at the time. And no wonder! The XK had through-the-lens (TTL) metering, automatic diaphragm lenses, and automatic exposure control. But, it had a lot more than that. Incredibly, it had shutter speeds from 16 seconds to 1/2000, with aperture-preferred, automatic exposure, metered-manual and full manual settings, as well. The photographer now had incredible options for exposure determination. The exposure could be set with a hand-held meter, by matching the needles in the viewfinders (like on the SRT101), or the camera could make the settings for you.

The XK had a complete information viewfinder, but it was a big change from that of the SRT101. This was quite a challenge given the various exposure modes. In the SRT101, the manually-set shutter speed appears on a scale on the bottom of the screen and two needles on the right-hand side match up by changing the f-stop and shutter speed. With the XK, this approach wouldn't work since the shutter speed could be manually-set or autoamtically-set. Minolta devise a screen that incorporated the two "scales" of the SRT101 viewfinder. First, the XK shows the manually selected shutter speed, but the speeds are no longer shown as a line-up across the bottom of the screen. The shutter speeds are now on the right-hand side of the screen, and the manually-set speed appears as a tab on the scale. The big change is that the same shutter speed scale has an additional needle that points to the recommended shutter speed (in manual mode) or to the automatically-selected shutter speed (in auto mode). Lastly, the XK viewfinder also shows the manually selected f-stop -- in a window on the top -- something missing in the SRT101.

On top of the new viewfinder (literally), the XK had interchangeable heads with several interchangeable screens. Plus, the XK had all the other bells and whistles available at the time -- mirror lock-up, DOF button, battery check, self-timer, and more. A completely new, titanium shutter was used, and the camera had a Sensi-switch which turns on the camera effortlessly -- just by picking up the camera. More than twenty-five years later, this camera has more features than most new SLR cameras.

A year later, Minolta produced another stunner -- the CL.

A collaborative camera with Leitz, the CL was designed by Leica in Wetzlar and made by Minolta in Japan. Minolta and Leica always had a love-hate relationship, with Minolta loving Leica cameras and designing several cameras after the Leica models (see above) -- and Leica hating the market share that Minolta was taking away from them. And as production costs continued to rise in Germany, Leica looked for ways to cut costs while expanding their market share. Leica decided to produce a compact Leica (CL) camera that would be less expensive than their existing models. But in order to keep production costs down to a minimum, they needed the camera to be manufactured by an outside company with hi-tech capabilities and low labor costs. They were able to reach an agreement with Minolta, and the CL was born. It's basically a miniaturized Leica M3 with the same bayonet mount. But what made the CL different was the built-in behind the lens meter! Originally, the lenses were supplied by Leica, but things evolved over time, and Minolta eventually made the lenses. The CL was sold in different markets, at different times as the Leica CL and the Minolta CL. Under the manufacturing agreement with Leica, Minolta was allowed to sell the new CL -- in Japan -- as the Leitz-Minolta CL. All of these variations were the same exact camera, but the supplied lens might be a Leica or a Rokkor. This leads to a lot of confusion. The major features include shutter speed and metering information displayed in the viewfinder, built-in rangefinder, interchangeable lenses, hot shoe, compact and lightweight. Sure, it lacked the auto-exposure of the CLE (see below), but it has a full range of shutter speeds (1/1000 to 1/2, plus B). It has a vertically-styled shutter, similar to the Minolta XE-7 (which was also a collaboration with Leica), but the shutter in the CL is completely battery FREE!

By the early 1970's, the 16mm camera market was so successful that Kodak decided it wanted a piece of the pie. It released its 110 camera line with an enormous media blitz. Millions of people, who had never heard of 16mm cameras, suddenly wanted a tiny camera. It resulted in the death of the 16mm camera, but Minolta was able to get into the 110 camera market immediately. It was easy for them because of their history with 16mm cameras. Unlike most 110 cameras, Minolta only made high quality 110 cameras, like the 110 Zoom SLR of 1976.

It was the first 110 in an SLR design, and only the second with a zoom lens. Fully-automatic, aperture-priority exposure. The lens was a 25 - 50mm (f4.5-16.0) with close-focusing capability (focusing to 11 inches). Speeds of 10 seconds through 1/1000. X (1/150) and B settings. Cds meter (not through-the-lens) with exposure compensation control. LED's in viewfinder warn of over- and under-exposure, and low battery power. Built-in lock on the shutter release, tripod socket, hot shoe, tripod socket, battery check, pop-out lens shade and cable release thread. And sharp, SHARP pictures to boot.

By the late 1970's Minolta was facing new chanllenges. The XK was a superb camera, with automatic exposure, but Minolta had stiff competition from other companies. Other manufacturers were producing cameras with convenience features similar to the XK, but that were significantly smaller and lighter. First, there was the Olympus OM-2 (1975), and then the Pentax ME (1977). Minolta got into the fray -- but with a twist. How about the world's first multi-mode camera which could be set for aperture-preferred or shutter-preferred expsoure automation? That's the XD-11 from 1977.

Plus, Minolta threw in a new, smaller body style with lots of new features. To take advantage of the new shutter-preferred features of this camera, a new line of lenses, the MD Rokkor-X series was introduced.

THE EIGHTIES

When Leica ceased the production of the CL in 1975 (which was actually made in Minolta's factories), Minolta was free to change the CL, and so they improved it to make the CLE of 1981.

And this time they completely dropped the "Leitz" from the name. It was slightly larger than the CL, but boasted TTL metering with both automatic and manual exposure modes. In addition, because it was now a silicone metering cell, the camera was able to offer TTL flash mode -- a breakthrough at that time and the first Minolta camera to offer this feature. The interchangeable lenses are basically the same, but a 28mm (f2.8) lens was added to the line-up. The camera also has a self-timer and hot shoe. Most cameras were in black, but a limited edition gold version was made to celebrate Minolta 3,000,000th camera.

Also in 1981, the top-of-the-line camera from Minolta, the XD-11, was four years old. Minolta decided that what was needed was a camera with an even easier exposure mode, and the X-700 was born.

The big difference is that this is the first Minolta SLR to offer programmed-exposure automation. It also offers aperture-preferred exposure control, metered manual, and manual modes. Thankfully, the shutter-preferred mode was finally laid to rest and gone for good. The X-700 added a new audible signal -- a beep -- when the self-timer was used and when the shutter speed was slow. There are little vents on the top of the pentaprism of the X-700 -- where the beeper is. The ON/OFF switch controls the beeper.

But the X-700 brought other changes as well. For example, the X-700 offers off-the-film (OTF) flash exposure mode. This is a big improvement over a regular flash, and even regular automatic flash, since the light from the flash unit is read through-the-lens (TTL) and is controlled by the meter in the camera. It compensates automatically for any filters or extensions that are on the camera (unlike the earlier X-series flashes that just set the correct shutter speed on the camera automatically and then read the light a few inches above the lens). This feature is GREAT for close-up work, and makes complicated calculations or adjustments a thing of the past.

Also in the early-80's, Minolta got into the disc camera market. It was easy for them because of their history with 16mm and 110 cameras. Unlike most disc cameras, Minolta only made high quality disc cameras, like the Minolta ac 101 Courreges.

In 1985, Minolta developed the world's first auto-focusing SLR -- the MAXXUM -- which was followed by many other auto-focusing SLRs -- from Minolta and from competitors. Unfortunately, unlike other camera companies, Minolta did not retain the lens mount used by its older manual-focus SLR cameras. This led to intense competition as other manufacturers got into the market and wooed former Minolta users. Since their old manual-focus lenses were no longer usable, Minolta had disenfranchised their loyal customers. A few years later, Minolta got into the digital camera market -- repeating the same disaster. Shortly after getting into the digital camera market, the stiff competition forced Minolta to merge with Konica -- another long-lived photographic company in financial trouble. But the marriage was short-lived. In 2006, Konica-Minolta officially announced that they would be dropping out of the photographic market completely -- a sad end to two of Japan's oldest and most innovative photographic companies. Fortunately for Minolta users, there are millions of used cameras and lenses that can be found -- repaired, if necessary -- and used. And Chinese companies, like Seagull, will be making Minolta-compatible cameras for years to come.

RETURN TO THE MANUAL MINOLTA HOME PAGE

COPYRIGHT@1995-2026 by Joe McGloin.

All Rights Reserved.

The material on this website is protected by US Federal copyright laws. It

cannot be copied or used in any manner without specific approval from the

owner.